HOW IT BEGAN...

|

Loretto in Taos

By Eleanor Craig, S.L. Director of the Loretto Heritage Center, Nerinx, KY The Sisters Early in 1863, Rev. Father Gabriel Usell, the then parish priest of Taos, New Mexico, recognizing the need of a convent and Sisters to instruct the young of Northern New Mexico, petitioned the church authorities to establish a colony of the Sisters of Loretto at that place. The founding Sisters' first housing was provided by the local pastor as an incentive for them to come in 1863. |

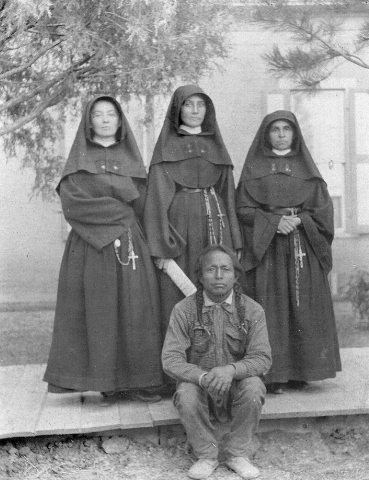

On October 15, 1863, the sisters left Santa Fe for Taos, the whole journey of seventy miles being made in carriages over very rough roads, through mountains, and along the Rio Grande. The sisters were obliged to walk nearly half the way. In those days such journeys were considered pleasure trips! Railroads were not thought of. The three sisters of that Order sent to Taos were the superior Euphrosyne Thompson, Sister Ignacia Mora and Sister Angelica Ortiz.

|

Euphrosyne Thompson (Elizabeth Catherine Thompson, 1839-1908) was 24 when she was sent from Santa Fe with two other sisters in 1863 to establish the school in Taos. Euphrosyne had frontier courage in her blood, being one of a pioneering family that had settled in Maryland in the 1630s and emigrated to Kentucky after the Revolutionary War. She was 19 when she traveled by steam boat and mule train from her Kentucky roots to Santa Fe in 1858.

Ignatia Mora (Pilar Mora 1842-1901) was schooled in her family's home in Albuquerque as a child; she attended Our Lady of Light Academy in Santa Fe for four years of high school, then worked a year with Euphrosyne in the Loretto day school. She entered the Loretto novitiate in Santa Fe in 1859 at the age of 17. She was 21 when she accompanied Euphrosyne and Angelica to Taos in 1863. There she taught Art and the Sciences until going to Las Cruces to take charge. She returned to Taos in 1898 for three years when in her mid fifties. She died in Santa Fe in 1901. |

Angelica Ortiz (Petra Ortiz, 1839-1913) was 24 when she was sent to Taos in 1863. She had been one of the earliest students at Our Lady of Light Academy in Santa Fe, and was one of the first to be received into the Loretto noviate in Santa Fe. She was 16 years old and among the first Hispanic women to join Loretto. She may have worked with Euphrosyne at the day school in Santa Fe from 1858 to 1863. She was with Euphrosyne and Ignatia Mora in Taos for only one year. She circulated from year to year among the Santa Fe academy, and the schools of Las Vegas, NM and Mora, serving with Euphrosyne in both Las Vegas and Mora. Angelica died in Santa Fe in the 50th anniversary year of the school she helped establish in Taos.

The School

|

On November 3, 1863, a school for girls was opened with an encouraging attendance. Two large classrooms held 80 to 100 students each, one for primary grades, the other for intermediate grades. In addition, there was a gathering hall and space for one of the sisters to teach private music lessons.

Each of the Academies was set up to be self-sufficient tuition and donations received from students' families and local supporters were the sole sources of income plus of course all the fundraisers, programs, socials, and so forth that brought in funds one nickel and dime at a time. |

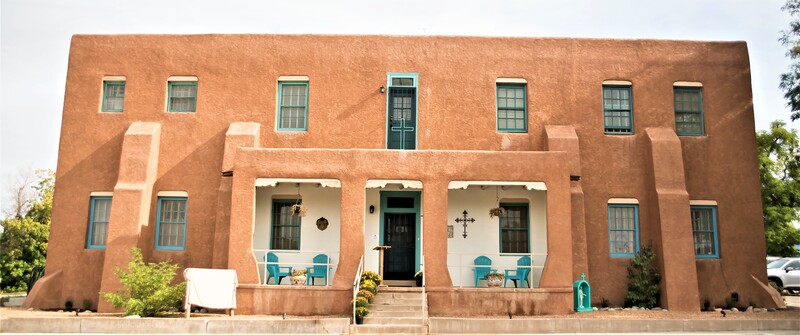

Over the years the sisters purchased additional acreage, built a two story adobe building in 1882, large enough to house three or four sisters and as many as 22 boarding students. When income fell short in a given year in Taos, the sisters cut back on comforts, delayed needed repairs, took in sewing and washing, took on more music students, dismissed paid help and took care of even more of the outfoor and indoor chores themselves. Finally, they sought paid positions with the public school system.

Thirty years after the sisters arrived, they individually signed contracts with the Taos School Board to teach public school classes for the short four or five months of the public school year. Each sister taught between eighty and one hundred children in ungraded classes. When numbers warranted, the School Board rented more space in the sisters convent and contracted lay teachers. Whenever one or more sisters were not under contract, they opened the private school to enhance their income with private tuition according to ability to pay.

Thirty years after the sisters arrived, they individually signed contracts with the Taos School Board to teach public school classes for the short four or five months of the public school year. Each sister taught between eighty and one hundred children in ungraded classes. When numbers warranted, the School Board rented more space in the sisters convent and contracted lay teachers. Whenever one or more sisters were not under contract, they opened the private school to enhance their income with private tuition according to ability to pay.

|

Shorty after their 50th anniversary in Taos, the sister opened high school classes under contract to the School Board. Some years the salaries and/or rent were not forthcoming for months. From the beginning of teaching for the public school system, the sisters in Taos were targets of disapproval, which gradually hardened into fierce opposition. The sisters saw great irony in this, since in many parts of the Rocky Mountain west, Lorettos were the first or among the first to qualify for public school teaching certificates.

|

In Taos, the courses for teacher training which were organized by the School Board were held at the sisters' convent, using the sisters' classrooms as demonstration sites. School Superintendant Mr. Montenar said more than once, "The Sisters' school is the only one worthy of the name and the best teachers in the country are those who had been taught by the Sisters." Nevertheless, in a School Board meeting in 1912, a majority of citizens voted for the candidate who opposed the sisters.

|

Religion and culture scholar, Kathleen Holschner, in her 2012 book Religious Lessons, writes that these conflicts culminated in the 1948-51 "Dixon Case," and resulted in the barring of sisters in religious garb from public school teaching in New Mexico. Holschner attibutes some of the animas against the sisters to the belief of Protestant Americans that nuns would of necessity force their students into the anti-democratic mindset of the Roman Catholic Church. A closer look at the cultural background of Loretto women teaching public school in Taos suggests they were not likely to behave like their European counterparts.

|

Despite Loretto's openness to democratic diversity, the public school connection continued to be uneasy, finally coming to an end in the spring of 1928. Our Lady of Gudalupe parish purchased the property and St. Joseph's went on as a parochial school with the Sisters of Loretto as teachers until the school closed permanently in 1973.